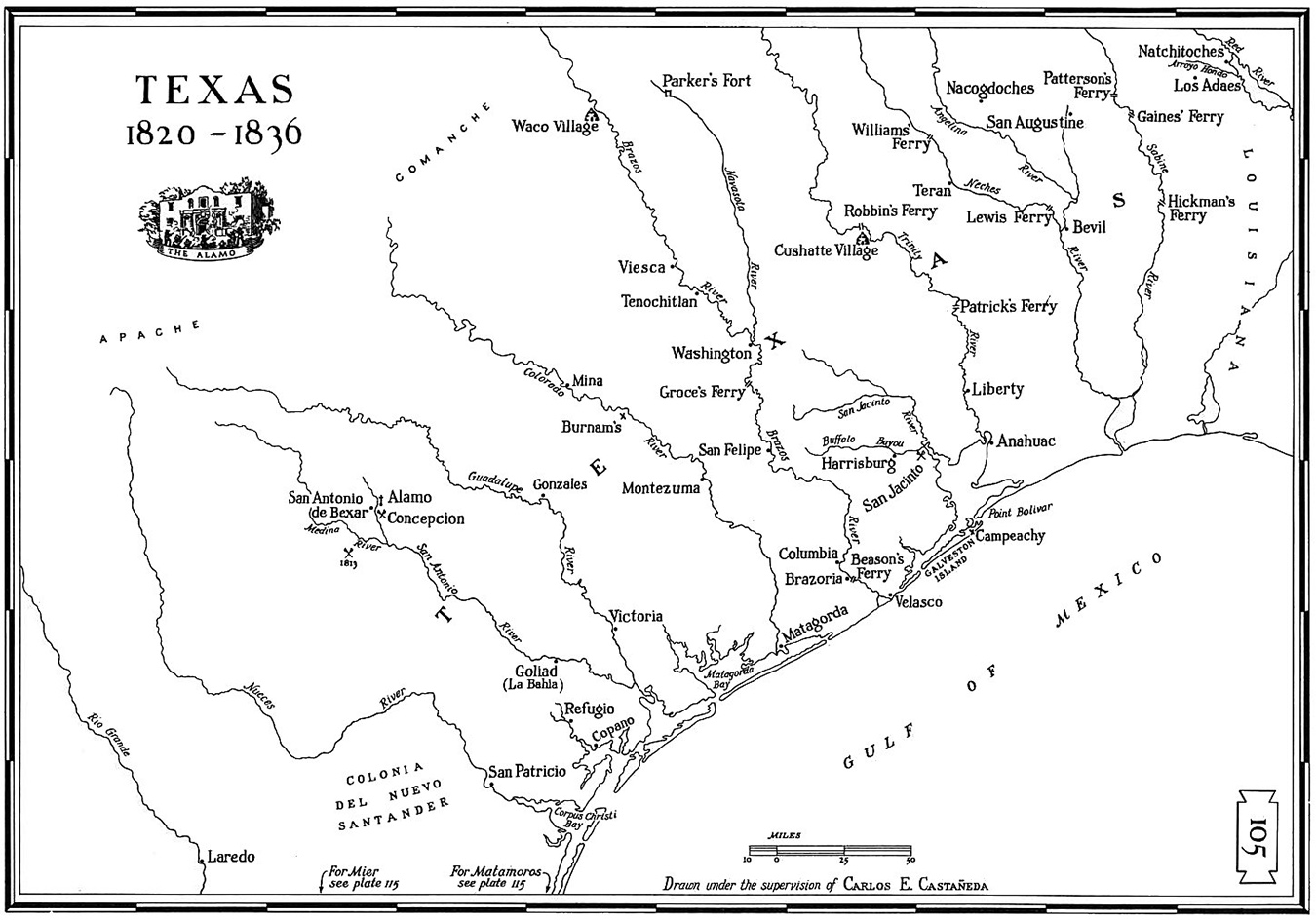

In the summer of 1835, William Magill scouted with the Rangers north to Parker's Fort (near the top center of this map) and as far as present-day Dallas. Bastrop appears as Mina (near the center). U.S. Map 1820, from www.mapssite.blogspot.com

Serving with the first Texas Rangers units in 1835, William Magill survived a battle, took a tragic shot

When the company of rangers set out from Bastrop in June 1835, the men were tracking Indians who had killed two settlers, the latest in a series of attacks. On about June 1, Indians attacked Amos R. Alexander and his son, who were driving a wagonload of supplies toward Bastrop on a primitive road coming from San Felipe. Their bodies were found a few days later by another settler, and when word reached town, Edward Burleson, a veteran of the War of 1812 and a colonel of militia since 1832, raised a squad of men who investigated the site and buried the bodies.

William joined the militia unit led by Robert Coleman, the town’s alcalde, or administrator under the Mexican system of government. Described as a firebrand from Kentucky who was eager to fight Indians, Coleman enlisted about twenty-five men.

His unit and Burleson’s joined another from La Grange, under the command of John H. Moore, bringing the total to sixty-one men. They headed north, and Burleson tracked a group of about eight Indians but lost all trace of them after a hundred miles. They had made camp for the night, when John “Bayt” Berry, who had gone out hunting, returned with a solitary Caddo Indian. Berry was a blacksmith in Bastrop and a distant cousin to William.

Accounts vary about the Caddo Indian, Chief Canoma. One historian writes that Texans employed him as a negotiator, and another says he was considered friendly. But John H. Jenkins, an early Bastrop settler who wrote a memoir, called him “a notorious glass-eyed Caddo who had before been caught with thieving parties.”

Canoma had information for the rangers. The historian Stephen Moore writes that settlers had asked him to begin peace talks with some hostile Indians and persuade them to return two small children taken captive. Canoma related that the Indians were willing to make peace with settlers along the Brazos River, but not with settlers along the Colorado River, and that a band was moving toward Bastrop.

Canoma was traveling with a group of eight or ten Indians, and as he led the rangers to their campsite, his companions fled. The rangers found two shod horses at the camp and surmised that these had been stolen from townspeople. Burleson’s men captured all of the Caddos, and the rangers discussed what should happen next.

Accounts agree that Coleman wanted to kill the Indians on the spot, but that Burleson wanted to take them back to Bastrop for a trial. Jenkins wrote that two contemporary sources said Canoma presented the rangers with a written certificate from settlers of Sterling Robertson’s colony stating they had hired Canoma’s band to recover some lost or stolen horses. “Burleson was satisfied of his loyalty, but the men, already angered at finding shod horses, believed that the other seven Indians had betrayed the Robertson citizens and were on their way to the mountains,” Jenkins wrote.

With the officers divided, the question was put to the men for a vote. The rangers voted two-to-one in favor of killing all of the prisoners except Canoma’s wife. Several men volunteered for the task, and historian Mike Cox writes that “Coleman cheerfully joined the firing squad.”

Jenkins wrote that this killing ensured the Caddos’ enmity toward Bastrop: “When the true facts about Canoma’s band were learned, they ‘were ever lamented by the chivalrous and kindhearted Burleson.’ The rest of the Caddo tribe declared an unconditional war on the Bastrop colony, but remained friendly to the Robertson colonists.”

It is not known how William voted in this fateful matter. Although he was serving in Coleman’s unit, he greatly admired Burleson and would serve under his leadership in future battles. One of the sources Jenkins cited was John Henry Brown, a prominent Texas historian who came to Texas as a teenager in 1837. Brown knew William Magill personally and writes that he heard many stories from him.

A Kentucky rifle allowed one shot and had to be loaded through the muzzle. Someone who practiced could reload quickly, but this could not be done on horseback.