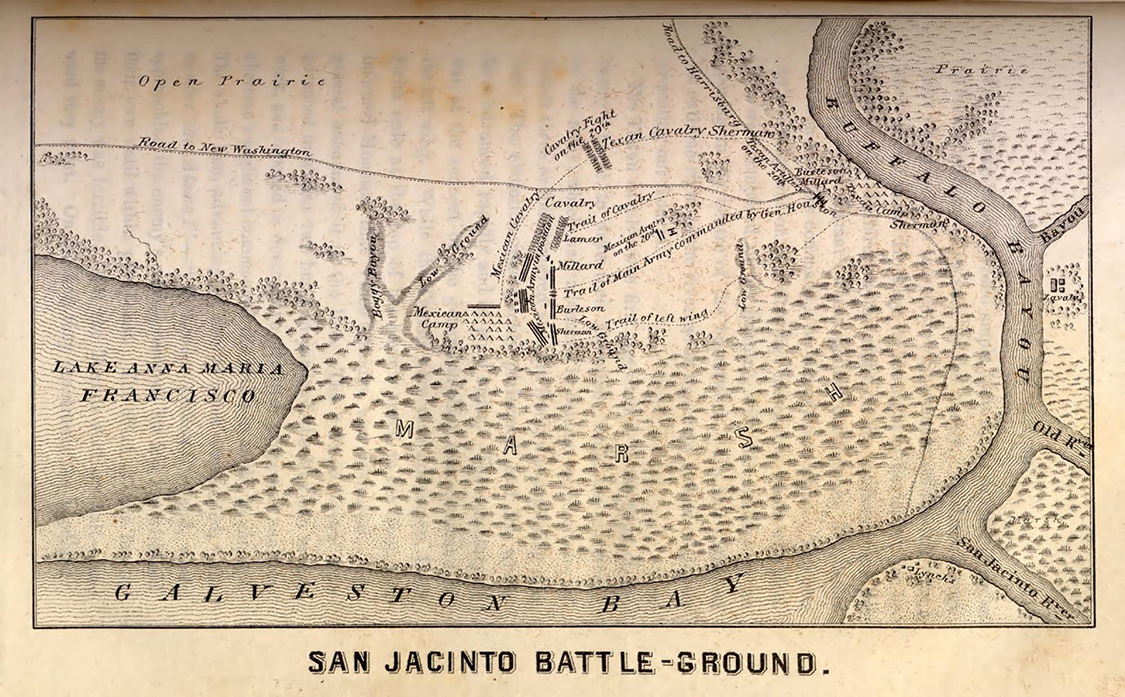

The Mina Volunteers were stationed at the center of the Texas lines, represented by the dark dashes labeled "Burleson" in this map of the battle against Mexican troops at San Jacinto on April 21. Map from www.sonofthesouth.net

William, elected second sergeant for the Mina Volunteers, fought in battle at San Jacinto

On February 28, 1836 the Mina Volunteers regrouped as thousands of Mexican troops began moving toward the settlements to put down the revolt in Texas. About two weeks earlier, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna had massed 6,000 soldiers at San Antonio.

The Mina Volunteers elected Jesse Billingsley captain, and among the other officers, chose William Magill as second sergeant. The company marched to Gonzales, where it was mustered in to the army as Company C of the 1st Regiment of Volunteers. Edward Burleson, who had joined up as a private, was chosen colonel.

In Gonzales, news arrived of a disaster. The Alamo had fallen, and all its defenders were dead, either killed in battle or executed afterward. Susannah Dickinson, twenty-two years old and with a fifteen-month-old baby, had stayed in the Alamo with her husband, Alamon, during the siege. The Mexicans sent her and a slave owned by William Travis to carry the news back to town. The loss was heavy for Gonzales, as many volunteers had responded to pleas from Travis and Jim Bowie for reinforcements. The town was filled with wailing and mourning, for most of its men had been killed.

General Sam Houston arrived at Gonzales March 11 and gave a stirring speech at DeWitt’s tavern. The provisional government had named him commander of the volunteers, and after the Alamo fell, he ordered a quick retreat to the east. Captain Jesse Billingsley wrote later that he objected to the order, but that Houston assured him the unit would move only a couple of miles down the road.

In an article in the Galveston News September 19, 1857, Billingsley wrote they were kept marching all night, and during a rest at dawn, “our ears were saluted with the noise of barrels of powder, sprits, &c., exploding in the burning of Gonzales. All the stores for the supply of the Army had been placed there, and our sudden retreat in the night left all the property and worse than this—left all the families in the neighborhood at the mercy of our implacable enemy, none being aware of our sudden, and, to them, inexplicable move.”

Account draws on viewpoints of men from Bastrop

This article draws mainly on accounts of men from Bastrop who were in the battles or helped civilians as they fled the Mexican troops. Capt. Jesse Billingsley's criticisms of General Sam Houston may be a minority viewpoint, but as he talks of conferring with with junior officers, it's likely that William Magill shared, or at least heard, these opinions while serving as a sergeant under Billingsley.

Though Noah Smithwick served as a scout and missed the battle at San Jacinto by minutes, he gave moving accounts of the Runaway Scrape and the scene at the battleground; he lived in Bastrop and was a friend and associate of William's for thirty years.

Men saw families fleeing in terror, often on foot, as the volunteer army marched east, with civilians behind them and ahead of the Mexican army. “There were no vehicles in the country, even if they had time to avail themselves of them (for at that day all had come to the country by water). There were also rivers to cross; and, for tender females with children, that was almost impossible,” Smithwick wrote. Houston sent volunteers to help the fleeing settlers, and at the Colorado River, the army paused for two days to let civilians cross ahead of them.

That group would end their flight near the San Jacinto battlefield. The mass flight of settlers, called the Runaway Scrape, divided into three main groups. One, the farthest south, reached safety in Louisiana. The group farthest north kept traveling well past the victory at San Jacinto, while the middle branch found itself camping by the battlefield.

Houston continued marching the volunteers to the east, their numbers swelling as other companies joined up, peaking at about 1,200. Hundreds of militia volunteers also left, often just temporarily to help their families. Billingsley wrote that some left also out of frustration that Houston kept them retreating even when they encountered opportunities to fight.

“Having but scanty clothing and many of us without shoes, and our property gone we were naturally eager for the fight, knowing that nothing but victory could save us,” he wrote. The junior officers agreed among themselves that when the road forked, they would take the route toward Harrisburg to meet the Mexican army, rather than toward Nacogdoches and continued retreat.

Near Harrisburg, the Texans, now numbering about 900 men, learned that Santa Anna had burned that town. Trying to gain a position against his troops, which were on the move, the volunteers marched all night. They had stopped for breakfast when fresh news arrived and, Billingsley wrote, “we immediately dropped the preparations for breakfast, seized our arms and hastened on.”

The first skirmish began when the Texans had just made camp. After Santa Anna came upon them and fired artillery, a company of Texans was sent out on the field. Seeing the men “under a heavy fire and receiving no orders from Gen. Houston to go to his (the officer's) support, I determined to go voluntarily, and accordingly led out the first company of the first Regiment …” Billingsley wrote. The entire regiment then followed, with Burleson in command.

The officers ignored Houston’s order to countermarch and succeeded in driving the Mexicans back behind their breastworks. Billingsley wrote, “when finding we were likely to gain the advantage, he withdrew his forces to the adjacent bank of the San Jacinto.” Santa Anna began building fortifications there, about three-fourths of a mile from the Texans’ camp.

A cannon from 1836 is displayed in Austin.

The battle had stopped for the day, and Billingsley wrote that the junior officers agreed among themselves that night that they would attack the next day, whether Houston gave the order or not.

The next day, April 21, Houston hesitated to go into action, questioning Burleson repeatedly about whether his volunteers would stand and fight. At about 3:30 p.m., the Mexican camp was quiet during siesta time and apparently had not posted sentries. Houston gave the order, and the Texans attacked with cries of “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Fannin and Goliad!”

The infantry fought with Kentucky hunting rifles, and the cavalry with shorter carbines; they had pistols and Brown Bess muskets, which had a smooth bore and were less accurate at a distance. At close range, the frontiersmen fought with their knives and rifle stocks.

In eighteen minutes, the key battle of the war for independence was over. The Mexican army broke and fled, Santa Anna somewhere among them. He was found hiding several days later, dressed as a common soldier. The Texans suffered only nine deaths, one of them a man from Bastrop. Billingsley had a wounded hand, and Logan Vandeveer, a private, was listed among the seriously wounded, though he survived. Houston was wounded by a shot in the ankle that shattered the bones.

More than a thousand Mexicans were dead, and there was some plunder of the army’s supplies and silver. Smithwick wrote that the bodies were lying in heaps, and that buzzards and coyotes went for the horses.

The victory at the San Jacinto River assured that Texas would become independent from Mexico, and it generated public support within the United States for the new Republic of Texas to join as a state. Fearing that Mexican forces would regroup and attack again, many settlers sent their families back to the United States for a year or longer.